The Hidden Risks Teams Miss

Most AI teams take ethics seriously at the point of data collection. Consent flows are reviewed. Compliance checks are completed. Data sourcing is documented, approved, and signed off. By the time a dataset is delivered, there is a quiet confidence that the hardest ethical work is already done.

That confidence is exactly where the risk begins.

Ethical issues in AI rarely surface at the moment of collection. They emerge later, quietly, gradually, and often invisibly. Not during onboarding. Not at delivery. But months or even years afterward, when the same data is reused, retrained, shared across teams, or deployed in contexts no one explicitly planned for at the start.

This is the part of the AI data lifecycle most teams underestimate.

Once data enters real workflows, it stops behaving like a static artifact. It moves across systems, gets reshaped by annotation and filtering, and is reused across models, geographies, and business goals. Each transition introduces small shifts that seem harmless in isolation. Over time, they compound into meaningful ethical risk.

This blind spot shows up most clearly in long-lived, high-reuse datasets. Image datasets are repurposed across multiple computer vision tasks. Video datasets evolve as objectives change. Text corpora quietly becomes training fuel for large language models, often without revisiting original consent. In these systems, data travels farther, lives longer, and changes more than most teams initially expect.

This is why managing consent throughout the dataset lifecycle matters as much as ethical sourcing itself.

Why Ethics Feels “Done” After AI Data Collection

Ethics often feels complete after collection for a simple reason. It is the most visible checkpoint in the AI lifecycle. Consent is captured. Legal reviews are completed. Documentation exists. There is a clear moment where teams can say, “We did this responsibly.”

That sense of closure is understandable. It is also incomplete.

The Comfort of Ethical Checkboxes

At collection time, ethics are tangible. Teams can point to contributor agreements, approved sourcing channels, and compliance frameworks documented within internal policies and compliance guidelines. For image datasets, this may mean confirming image rights and consent. For video datasets, ensuring recording permissions and usage clarity. For text datasets, validating contributor awareness and scope.

Once these steps are complete, attention naturally shifts to model performance, delivery timelines, and downstream integration. Ethics fades into the background, not because teams stop caring, but because it feels settled.

That confidence assumes ethics behaves like a one-time decision. In reality, ethics is a condition that must be actively maintained, not a checkbox that stays checked.

Where the Blind Spot Begins

The blind spot appears the moment data starts moving.

Post-collection AI data ethics is not about whether sourcing was responsible. It is about whether ethical intent survives what comes next. As datasets enter annotation pipelines, quality filters, reuse cycles, and retraining loops, ethical risk does not disappear. It evolves.

Because these changes happen incrementally, teams rarely notice them in real time. By the time something feels off, systems have already moved far beyond their original context.

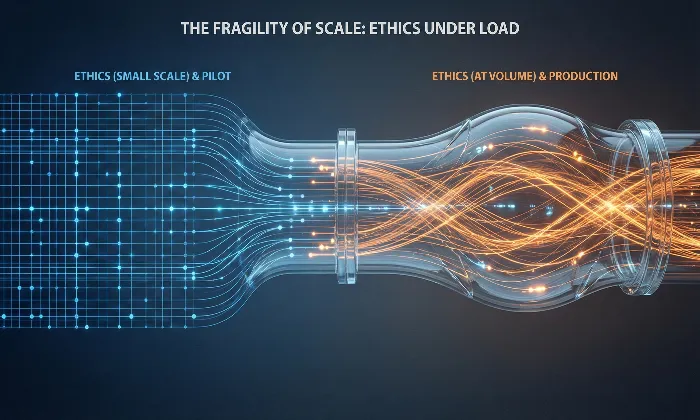

Once that sense of ethical completion sets in, the real work begins, and most teams do not see it coming.This pattern reflects a broader systems issue explored in ethical AI at scale as a systems challenge.

What Actually Changes Once Data Enters AI Workflows

After collection, data stops being “the dataset” and starts becoming infrastructure. It is touched by more people, repurposed across more objectives, and stretched across more contexts than originally anticipated.

This is where ethical risk becomes operational.

Annotation, Filtering, and Quiet Bias

Annotation is never neutral. Whether labeling images, tagging video frames, or annotating multimodal interactions, human judgment shapes how data is interpreted.

In image datasets, annotation guidelines prioritize clarity and consistency, which often means ambiguous images are removed using structured image annotation services. In video datasets, clips with poor lighting, motion blur, or background noise are filtered out during video annotation workflows. In speech and multimodal datasets, alignment and transcription decisions rely on audio annotation services and text annotation services.

None of these decisions feels unethical in isolation. Taken together, they reshape representation. Non-standard expressions, regional variation, informal behavior, and minority patterns are often the first to disappear, not because they are wrong, but because they are inconvenient.

This effect is especially pronounced in multilingual and cross-cultural datasets sourced through global contributor programs such as Crowd-as-a-Service data collection, where annotation frameworks must operate across cultures and languages.

Reuse, Retraining, and Scale

Reuse is where ethical complexity accelerates.

A dataset created for one purpose often finds new life elsewhere. An image dataset collected for object detection may later be used for facial analysis. A video dataset initially designed for activity recognition may later inform safety analytics through driver drowsiness video datasets. A text corpus assembled for moderation can later fine-tune LLMs using prompt and response datasets.

None of these secondary uses is inherently illegal or unsafe. The ethical issue is not reuse itself, but misalignment.

When contributors consented to one type of use but were never informed about another, ethical clarity weakens. Each retraining cycle amplifies earlier assumptions, embedding them deeper into new models and applications.

As reuse becomes routine across teams and regions, ethics quietly shifts from an active question to an unexamined assumption. That is when risk compounds fastest.

These workflow changes introduce a deeper issue. The original terms under which data was collected begin to drift out of alignment.

Consent Does Not Age as Gracefully as Data

Data is durable. Consent is contextual. Over time, those two drift apart.

When Original Consent Stops Matching Reality

Consent drift occurs when data collected for one purpose is reused in ways contributors never anticipated.

Contributors may agree to provide images for general computer vision research. Years later, those same images might be used in different model contexts, across regions with different privacy expectations, or as part of multimodal systems they were never told about.

The use may be legal. It may even be safe. But when contributors lose visibility into how their data evolves, ethical clarity weakens.

This dynamic is increasingly discussed in research on representational drift in AI systems.

Consent in AI systems rarely fails loudly. It fades quietly as systems scale.

Contributor Rights After Collection

Contributors remain part of the ethical equation long after onboarding ends. Expectations around dignity, transparency, and informed use do not expire when a dataset is delivered. This is why contributor workflows are often supported through structured onboarding systems such as Yugo, the AI data platform, where consent, metadata, and audit logs remain accessible over time.

Without ongoing visibility into how data moves and changes, ethical intent becomes something teams explain later instead of something they design for upfront.

Consent complexity is conceptual. Deletion is where it becomes structural.

Deletion Is Where Ethical Intent Gets Tested

AI data deletion challenges are structural, not philosophical.

Deleting a source file is straightforward. Deleting its influence is not.

In real systems, data exists across backups, derived datasets, annotation layers, and model training pipelines. Image datasets are augmented. Video data is segmented and relabeled. Text data is tokenized and embedded into model weights.

Removing one file does not automatically remove its downstream impact.

Deletion also collides with operational reality. Multiple teams may rely on the same dataset. Models may already be deployed. Retraining introduces cost, time, and performance trade-offs.

This complexity is common in large-scale speech datasets such as call center speech data or in-car speech datasets that are reused across teams and regions.

Ethical maturity shows up not in promises of perfection, but in clarity about limits, traceability, and response processes.

Deletion reveals maturity, not perfection.

Meaningful deletion only works if access is controlled in the first place.

Security, Access, and Data Sensitivity After Collection

Data does not become less sensitive after collection. In many cases, it becomes more sensitive as access expands.

As datasets move across teams, regions, and partners, access creep introduces ethical risk. Each new assessor brings different assumptions about consent scope and usage boundaries.

For image and video datasets, expanded access increases repurposing risk, especially when contributors consented to research use, but data later support commercial products. For LLM training data, widespread reuse can blur the line between approved fine-tuning and unreviewed inference applications.

Role-based access, audit logs, and controlled environments are not just technical hygiene. They are ethical AI data practices. Governance without enforcement remains aspirational.

Enforcement requires visibility.

Metadata in AI data ethics is not overhead. It is what makes ethics enforceable over time.

Metadata preserves context, including where data came from, what contributors agreed to, what restrictions apply, and when reuse requires re-evaluation. Without it, teams rely on assumptions and tribal knowledge.

With structured governance workflows, where metadata travels with datasets from collection through delivery, teams can audit, trace, and respond to ethical questions with confidence.

This need for lifecycle governance is reinforced in recent AI governance research

and supported by open-source governance frameworks

Where did this data originate? What was it approved for? Can it be reused for a new model, geography, or modality?

Without metadata, governance remains aspirational. With it, ethical intent can persist as systems evolve.

The real question is not whether metadata matters. It is how teams operationalize it.

How FutureBeeAI Addresses Post-Collection Ethics in Practice

When teams struggle with post-collection ethics, the issue is rarely intentional. It is designed.

At FutureBeeAI, Post-collection ethics is treated as an operational responsibility, focused on what we control internally and what we influence through alignment and contracts.

Client Onboarding and Use Case Alignment

Post-collection ethics start before delivery. Use case alignment is not a courtesy. It is a requirement. Whether working with speech datasets, vision data, or multimodal collections, reuse boundaries and retention expectations are addressed upfront.

We focus on understanding not just what clients plan to build, but how data may be reused, shared, and retained over time. Using data for a different purpose does not automatically make that use unethical. But when contributors were never informed about that secondary use, ethical clarity weakens, even if the new purpose is valid.

That is why consent scope is reflected in licensing terms. Reuse boundaries, retention limits, and sharing restrictions are aligned with contributor expectations and embedded into agreements. Deletion handling is also addressed upfront, with clear expectations around traceability and response.

Internal Data Security and Access Discipline

Internally, access is limited by role and necessity. Different data types introduce different risk profiles, and controls reflect that reality.

Image, video, multimodal, and LLM datasets each carry distinct sensitivities. Access expansion is intentional, auditable, and aligned with ethical boundaries rather than convenience.

Traceability Across Data Types

Across image datasets, video datasets, multimodal datasets, and LLM training corpora, traceability is non-negotiable.

Data collection is conducted through structured tools that capture required metadata at the point of collection. Consent scope, context, geography, language, and usage boundaries are stored in a structured way so they can travel with datasets across workflows.

Metadata collection is intentional and proportionate. Collecting too little makes ethical oversight impossible. Collecting too much introduces a new privacy risk. The balance matters.

Traceability is not static. Contributors retain the ability to access and update their metadata over time, reflecting the reality that data often lives far longer than the moment it is collected.

This allows teams to answer critical questions later without guesswork. Where did this data come from? What was it approved for? Can it be reused safely?

Without traceability, ethics stay frozen at collection. With it, ethical intent can move forward as data moves, scales, and changes.

Ethics Is a Lifecycle Responsibility, Not a One-Time Decision

These practices are not unique to FutureBeeAI

They reflect what lifecycle ethics actually requires.

Post-collection AI data ethics calls for a mindset shift, not from carelessness to care, but from static thinking to lifecycle thinking. Ethical sourcing is necessary. It is not sufficient.

Ethics survives only when workflows are designed to carry context, consent, and accountability forward through reuse, retraining, access expansion, and time.

That means designing for auditability, questioning reuse assumptions, and treating metadata as non-negotiable from day one.

The teams that get this right are not louder about ethics. They are quieter, more disciplined, and more intentional about how ethics survive long after collection ends.

Post-collection ethics only works when workflows are designed for it, and those decisions are rarely one-size-fits-all.

If you want to discuss how this applies to your datasets, you can reach out to the FutureBeeAI team.